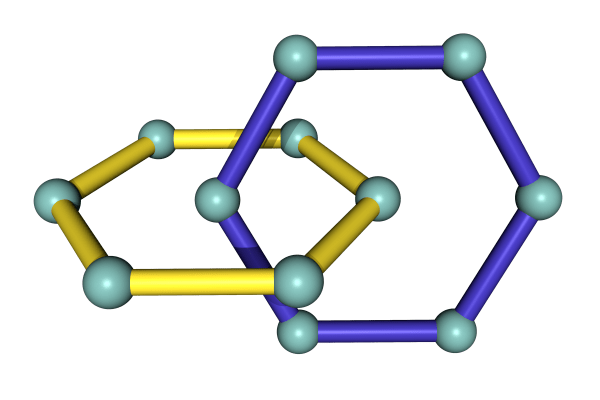

The hyperbolic plane is a geometry whose points are those of a disk, and the lines are circular arcs that meet the boundary circle of the disk at a right angle. Like so:

We see that the arcs in this figure cut out regions, and the central one looks like a deflated square. However, to the hyperbolic eyes the circles are actually straight, and all regions would be considered congruent squares. There is yet another difference to Euclidean geometry: These squares have corners with 60 degree angles, instead of the traditional 90 degrees. In fact, hyperbolic people can make squares with any angle less than 90 degrees at the corners, all the way down to 0 degrees. Then the vertices lie on the boundary of the disk, and we are getting what is called an ideal square.

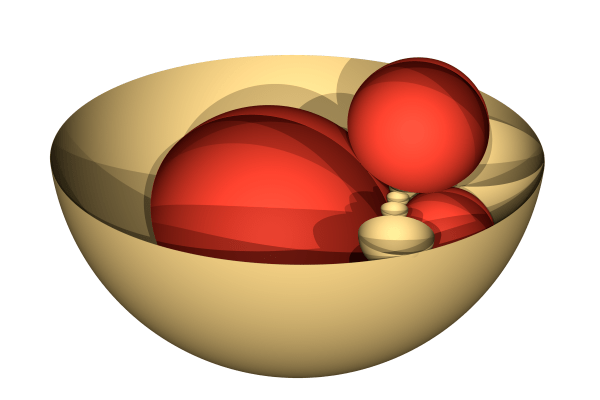

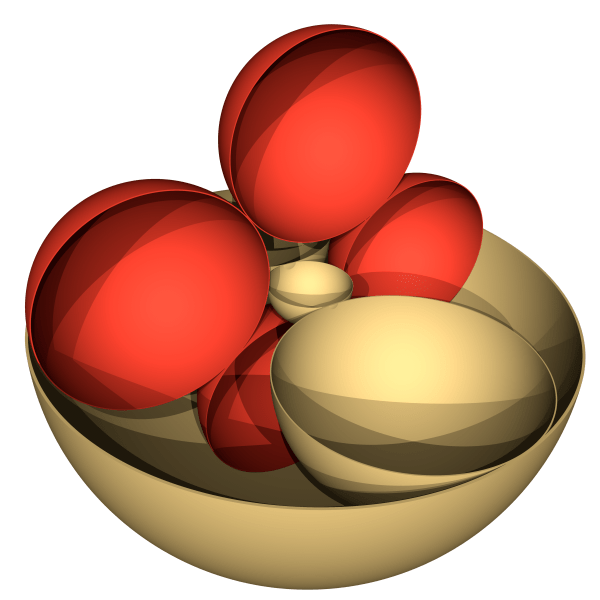

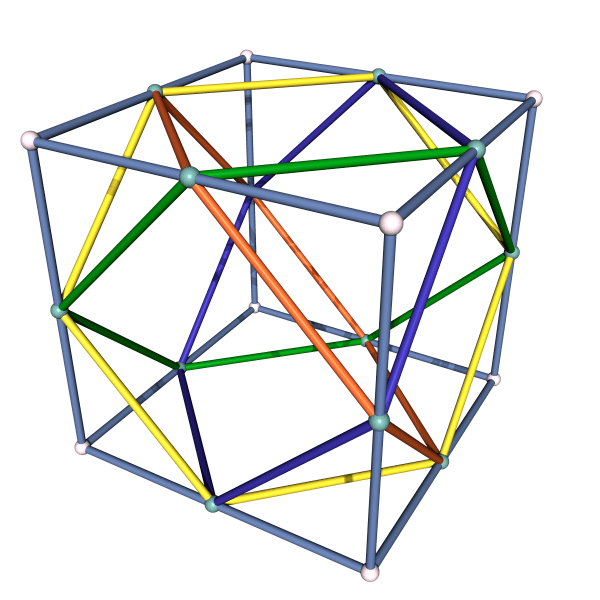

Of course there is also hyperbolic space, represented by a round ball. The planes are spherical shells meeting the boundary of the ball at a right angle. We can make cubes in hyperbolic space, with dihedral angles less than the traditional 90 degrees. This time, when the cube becomes ideal (i.e. when the corners lie on the boundary of the ball), the dihedral angles of the hyperbolic cube have shrunk down to 60 degrees.

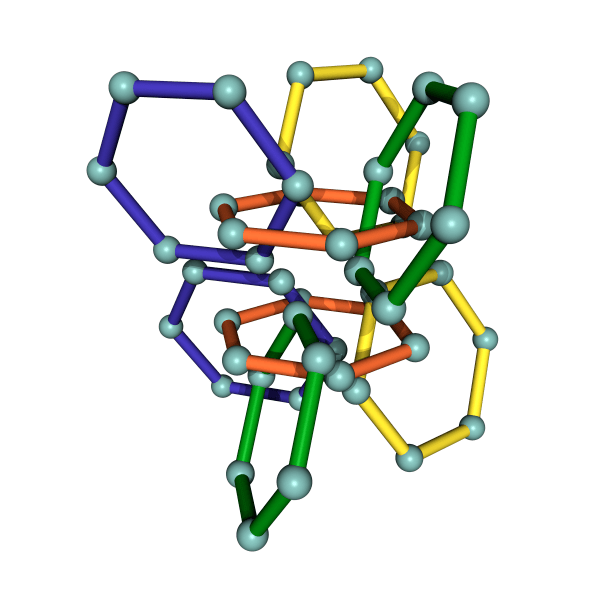

Because six such cubes will fit around an edge very much like six hyperbolic 60 degree squares fir around a corner, we are able to tile all of hyperbolic space with ideal cubes. Visualizing this is a challenge, as if we just draw all the cubes, we will just see a ball, and all the effort was in vain.

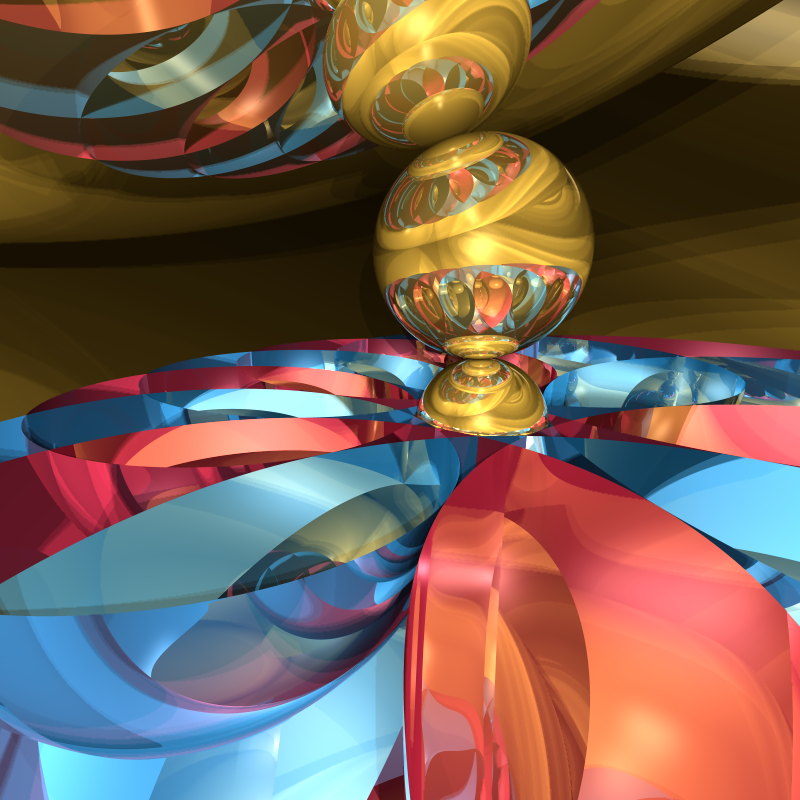

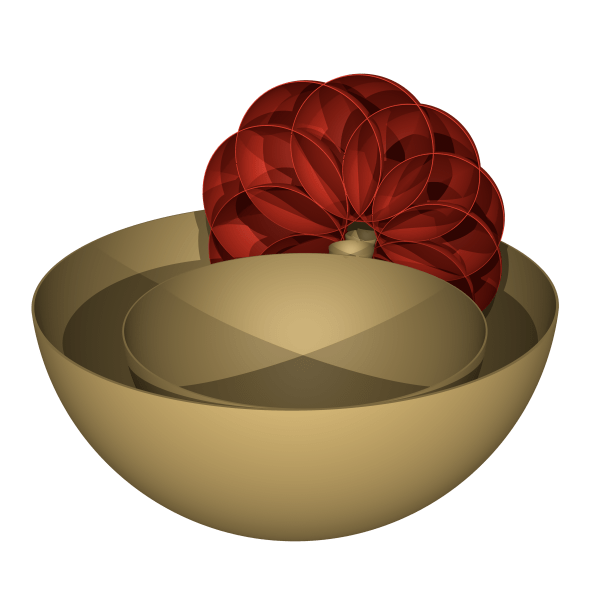

But we can leave out some of the cubes. If we start with the central ideal cube, and just take those cubes that can be obtained by rotating about the edges by 180 degrees, we get after a few steps the following object, shown as a stereo pair for cross-eyed viewing.

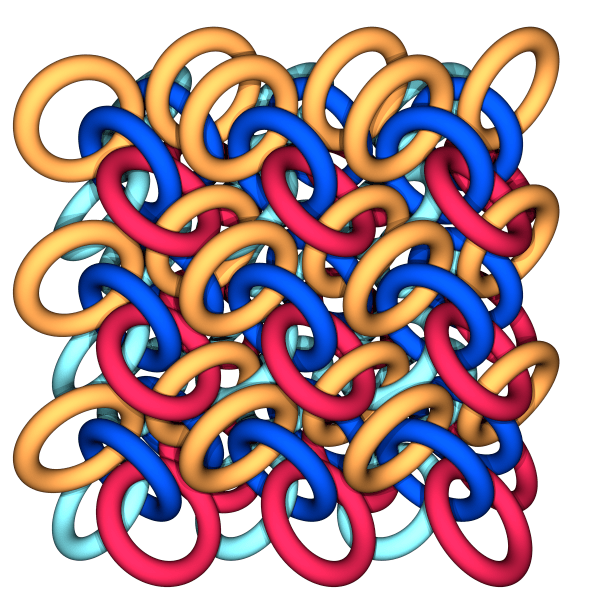

The final image is obtained by applying more such rotations, and making the material relective.