A good way to embarrass oneself is to go to a book store in a foreign country whose language one is not fluent in, and buy a book. I did this multiple times, at least in France, Spain, and the UK.

I typically tried to get by without saying a single word as not to reveal my complete incompetence, but the punishment for that can be unexpected. During one of my first visits to Paris, I went and bought the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade edition of Arthur Rimbaud.

The catch was that the very pretty cashier tried to initiate a conversation by smiling at me and saying “Ah, J’aime Rimbaud”.

I blushed, payed, and made my way out. Embarrassing.

But it brings us to the topic, Rimbaud’s Drunken Boat.

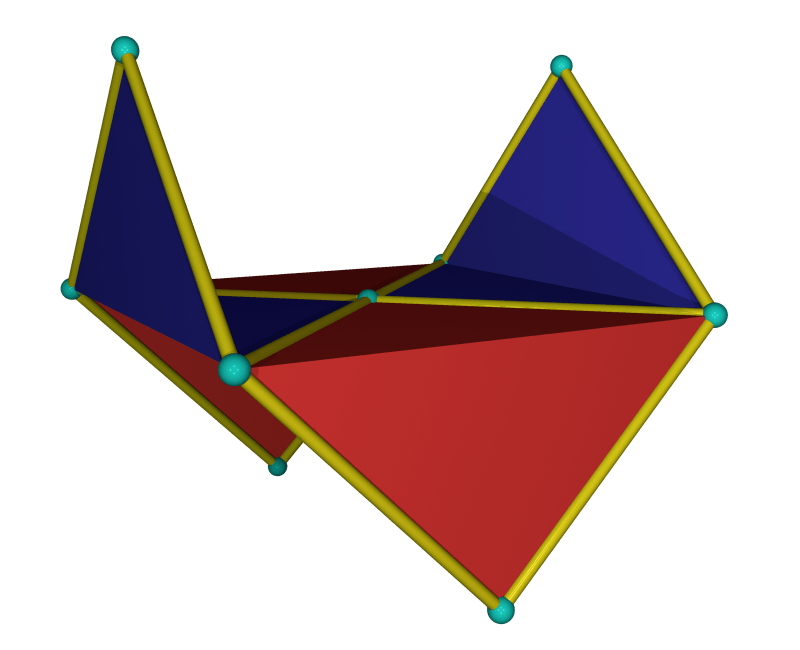

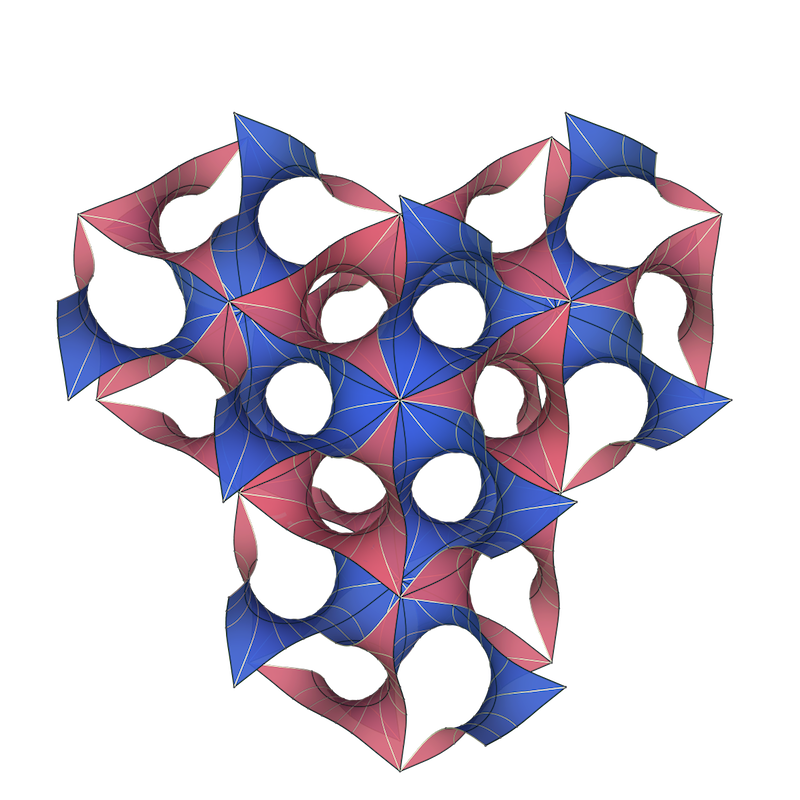

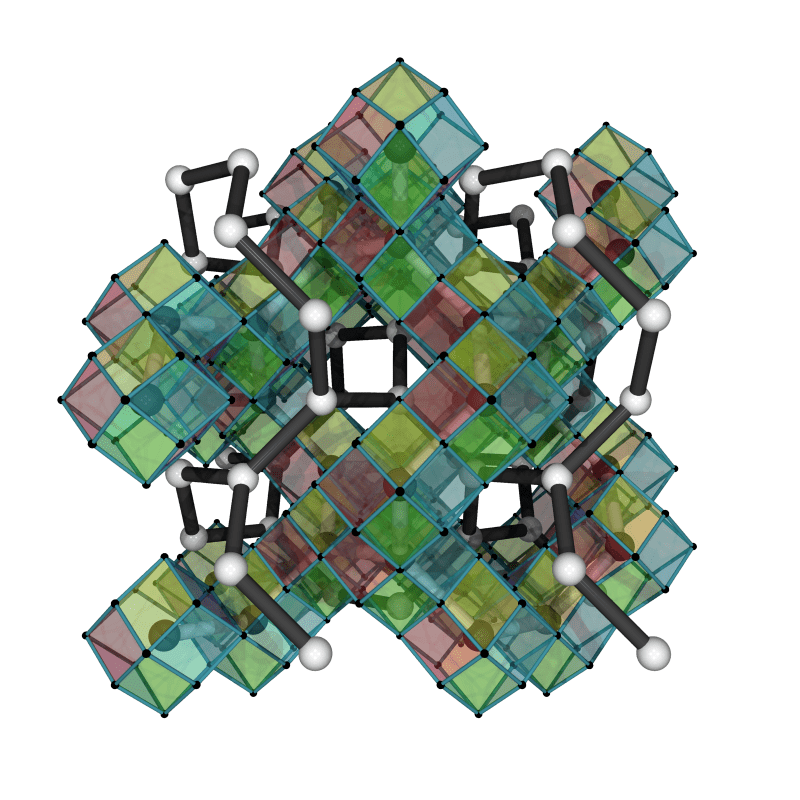

The image is this, and it does not look like a drunken boat. What we start with are the loxodromes I have talked about before. They are the curves a sober boat would trace out on the sphere when heading in a fixed compass direction. Laying down one of these loxodromic double spirals as a base using Malcolm’s clay printer looks like this:

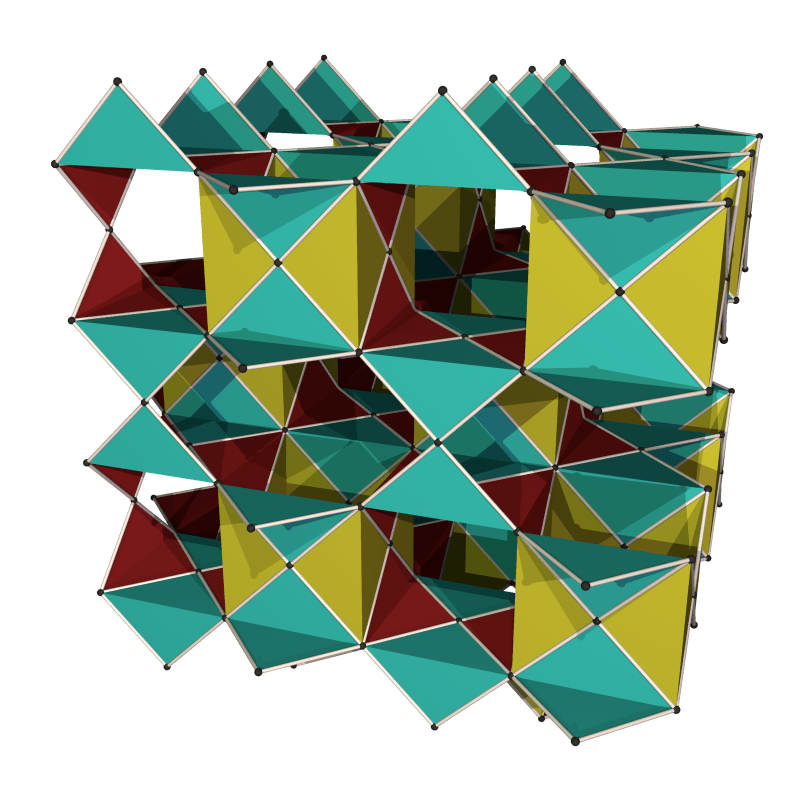

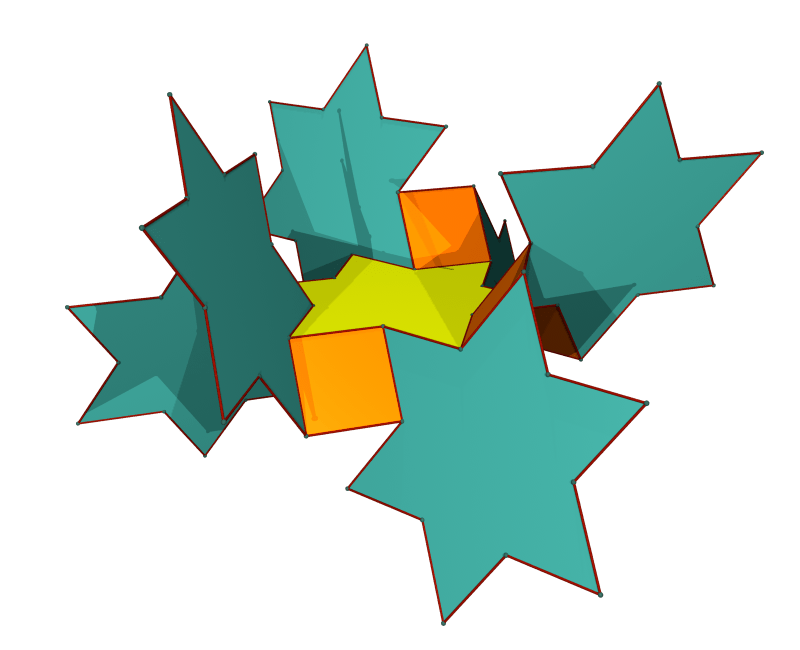

Then, moving up, we deform the loxodrome that represents say North-North-West slowly into North-West and then West, which corresponds to a meridian, and therefore a straight line in suitable stereographic projection.

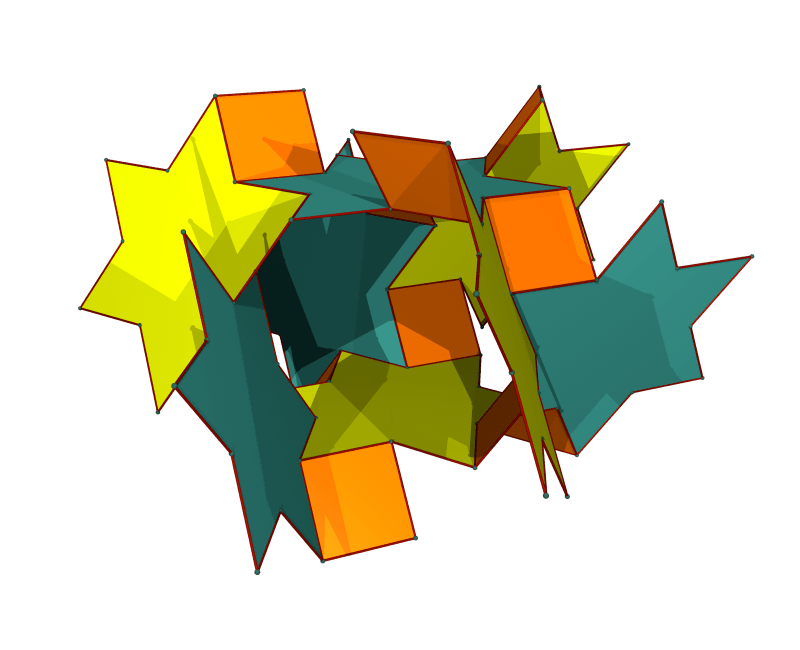

Then, even higher up on the sculpture, we change course to South-West and thus reverse the direction of the spirals.

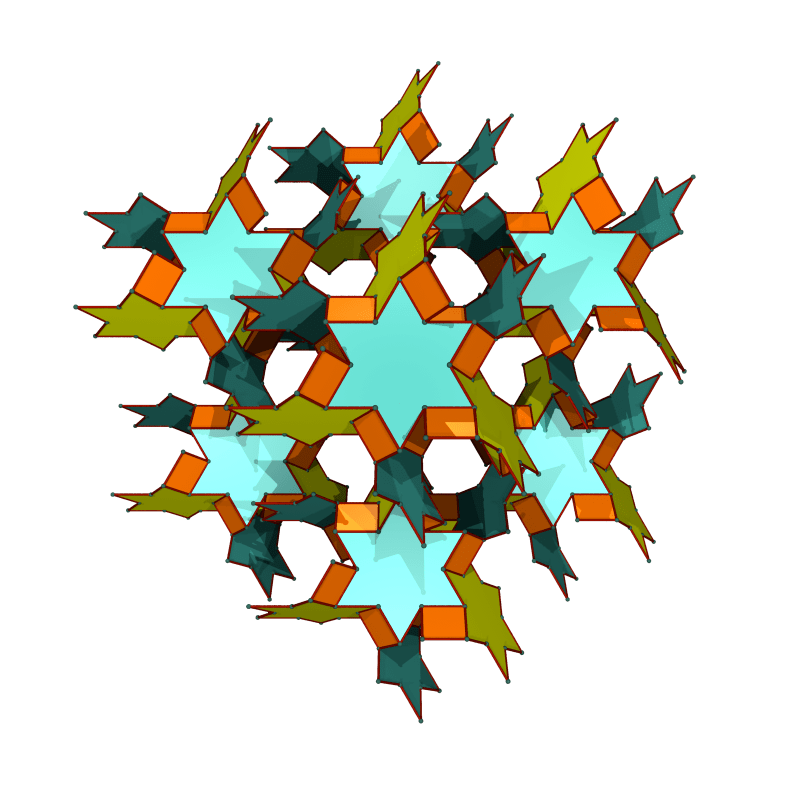

This was our first rough prototype. The next step will be to make this larger, cleaner, and slightly drunken, so that the loxodromes swerve left and right.

We’ll see shortly where we get…