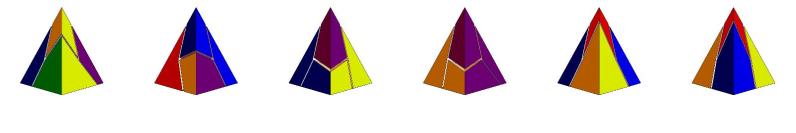

Alan Schoen’s Cubons and Tetrons make beautiful and interesting puzzles, but few people will have the patience to build them. So here is a workaround. I begin with simplified tetrons where the edges are divided either 1:2 or 2:1. There are just 4 of them, and they nicely fit together into a single tetrahedron. Here are three views of the same tetrahedron.

We now represent the tetrahedron by its edge graph K₄, and each cubons becomes a disk with three arrows placed on the vertices of this graph. The graph on the left represents the tetrahedron above.

An arrow pointing away from the center of the disk means that the corresponding edge of the cubon is long, and short otherwise. So instead of elaborately assembling tetrahedra, we can just place one of the four types of coins on the vertices of the graph so that the two arrows at the end points of an edge point in the same direction. As an exercise, try to find the tetrahedron below among the four graphs above:

Here is a little worksheet so that you can cut out coins in our new currency. You will have realized that these four coins correspond to the four rounded trillows. In essence, we are doing nothing but decorating the vertices of cubic graphs with trillows.

The same procedure works for simplified cubons. There are of course again just four of them, represented by the same set of coins.

Instead of trying to parse a 3D image, we decorate the edge graph of the cube with our coins. Below you see what the cube on the left above looks like. Try to find decorations of the graph that correspond to the other solutions.

Next time we will look into decorating other cubic graphs.

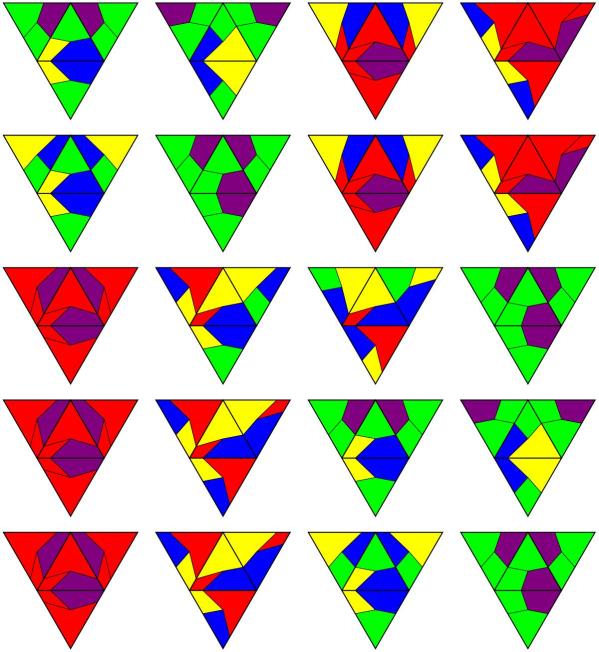

The tetrons are computationally much simpler than the cubons. For instance, we can again separate the 24 tetrons into 8 chiral and 16 achiral ones. Surprisingly, the 16 achiral ones can be assembled into four tetrahedra in exactly five different ways (up to rotations). Here they are, unfolded:

The tetrons are computationally much simpler than the cubons. For instance, we can again separate the 24 tetrons into 8 chiral and 16 achiral ones. Surprisingly, the 16 achiral ones can be assembled into four tetrahedra in exactly five different ways (up to rotations). Here they are, unfolded:

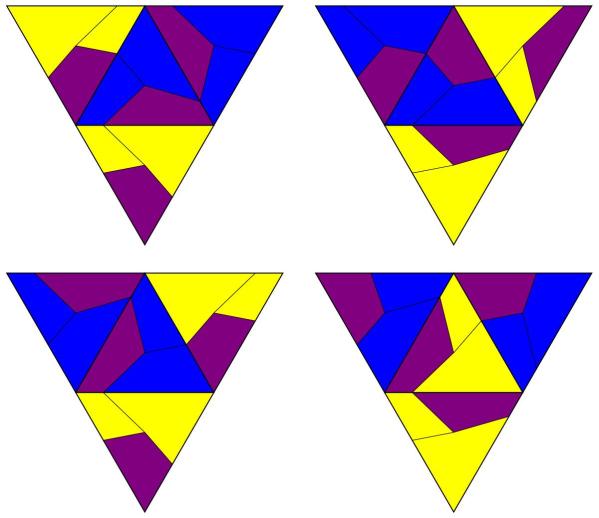

On the other hand, the eight achiral cubons obviously form four polar pairs (and can be assembled into a single cube). The remaining 16 symmetrical cubons can then be divided in four different ways into two sets of eight that are polar to each other, and that can both be assembled (in several different ways) into cube. Above are 3D solutions (one pair each column), and the nets are below.

On the other hand, the eight achiral cubons obviously form four polar pairs (and can be assembled into a single cube). The remaining 16 symmetrical cubons can then be divided in four different ways into two sets of eight that are polar to each other, and that can both be assembled (in several different ways) into cube. Above are 3D solutions (one pair each column), and the nets are below.