Take a long strip of paper, and fold it left over right, then left over right again, and so on, a couple of times.

Even if your strip is very thin and long, you probably won’t be able to do that more than six or seven times.

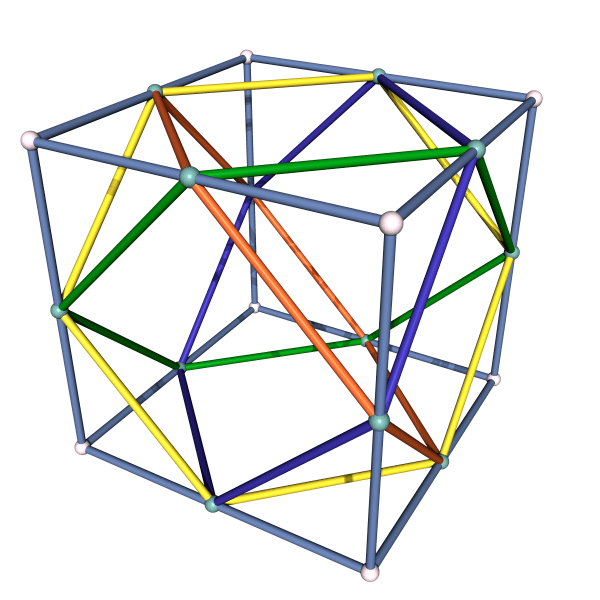

Then carefully unfold the paper so that each bent makes a right angle. What you get will look like this:

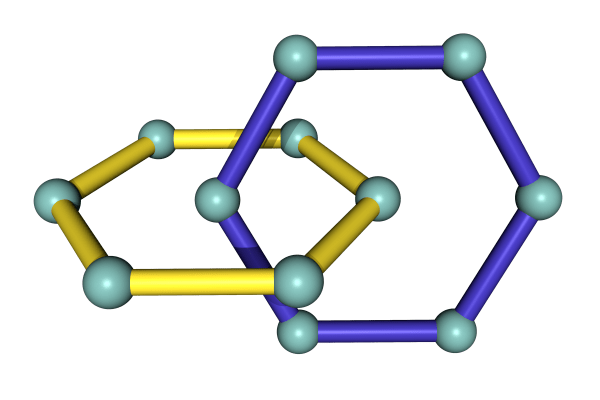

Another method leads to the same curves. Start with a curve consisting of two segments, making a right angle. Think of it as being a track you want to walk along. Things being difficult, you happen to swerve slightly to the right on the first segment, and on the second slightly to the left, meaning that instead of following the blue path, you walk the red path:

Now try again, this time starting with the red path that is four segments long (and colored blue below). The same happens, you alternatingly swerve right and left, creating the next (red) path. The curves will be the same ones as above.

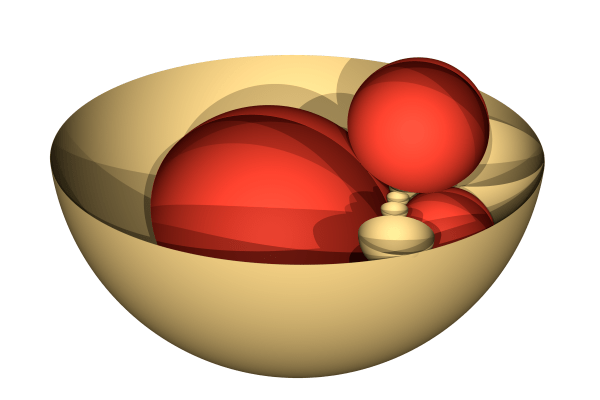

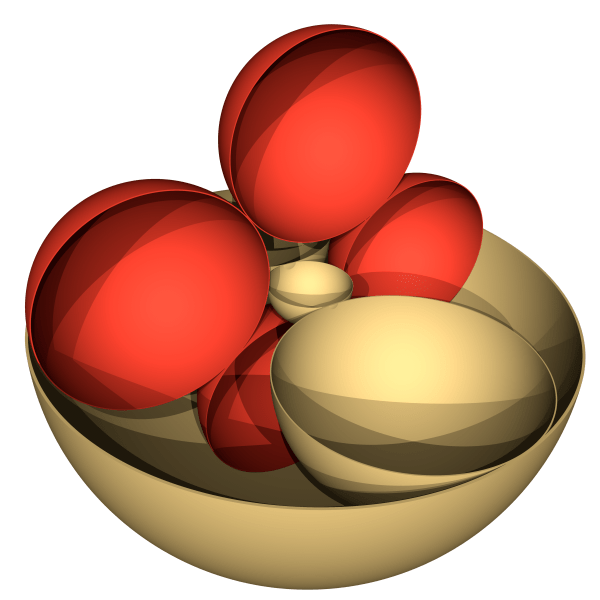

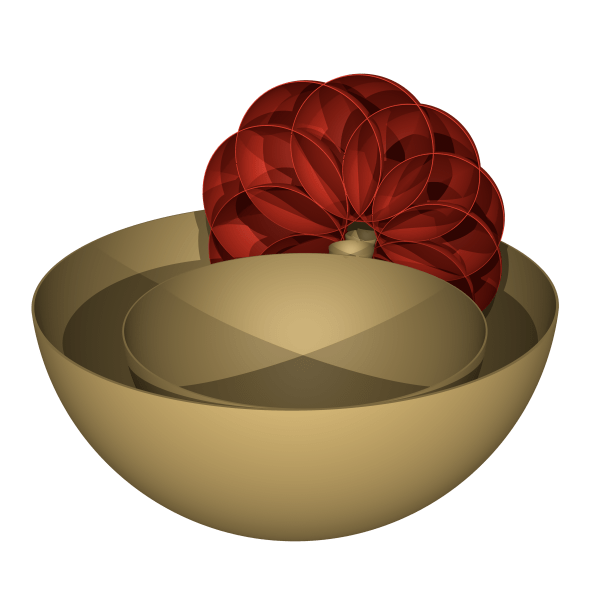

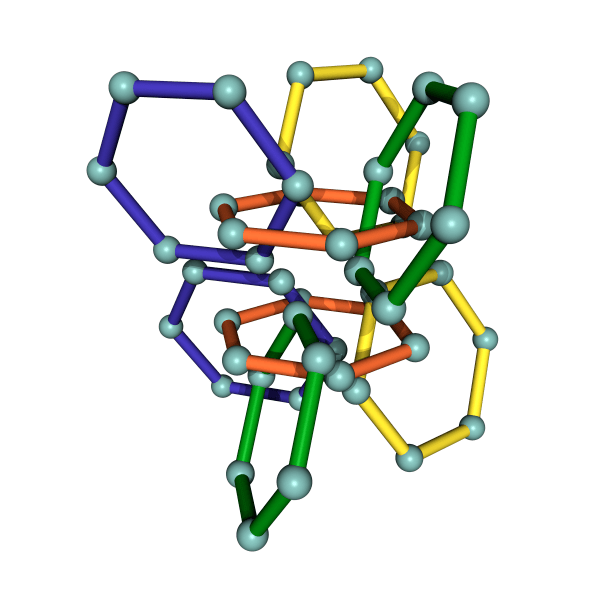

Is there any sense to it? Things get more amusing if you replace each segment by a square that has that segment as a diagonal. This turns the curves into polyominoes, as you can see for the first few cases below.

You will also see that these shapes start resembling a common dragon. If you keep folding a little while, more details emerge.

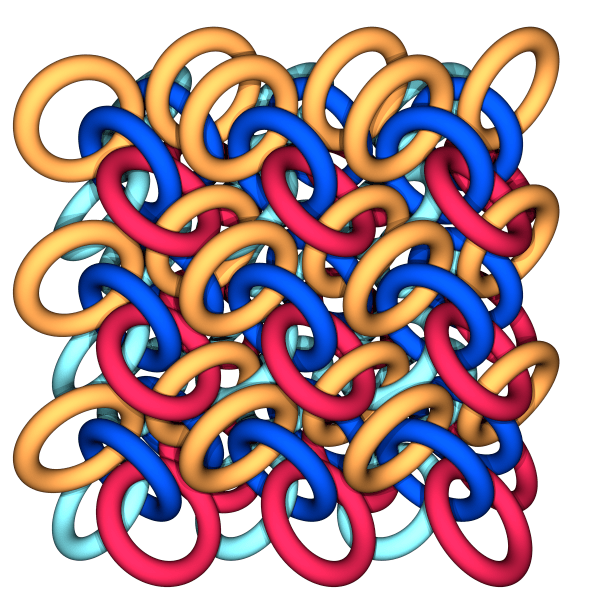

But it gets better. All these polyomino-dragons tile the plane, interlocking perfectly. Both the young dragonlings

and also the older, wrinkly ones:

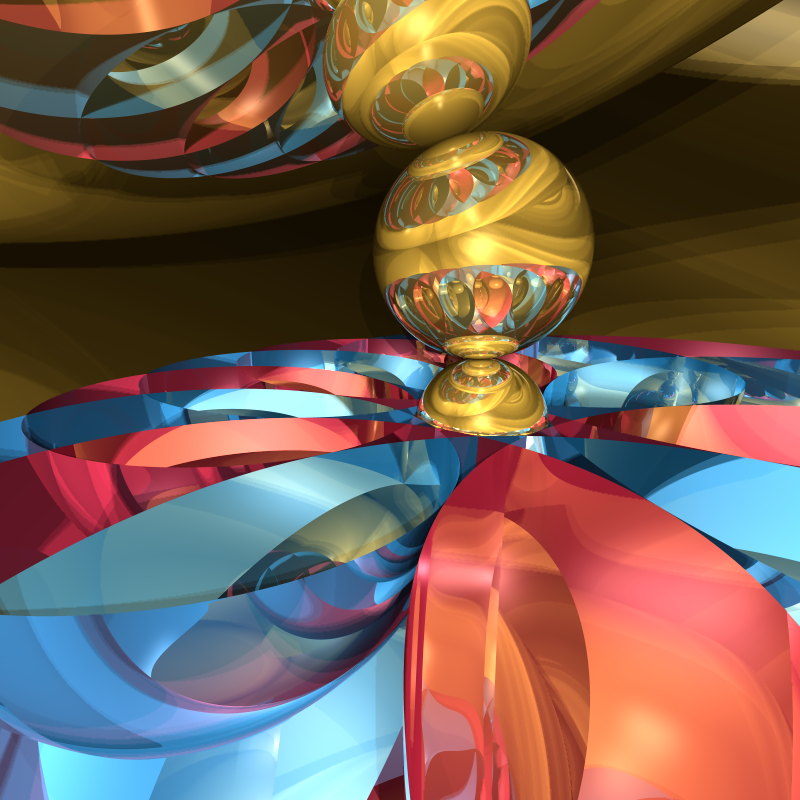

Now imagine stacking these dragons on top of each other, generation by generation. If I had the money, my mansion would look like that.