In Edwin Abbott’s Flatland, the struggles of a square in a 2-dimensional world to grasp the concept of a third dimension are a parable for our own struggles to grasp uncommon concepts. This is pushed to its extreme when the square tells the parable of linelanders struggling with the concept of two dimensions.

The obvious limitations of lineland make us quickly forget our own limitations.

Here is a little puzzle. Cut out the eight pieces up above, and arrange them into a circle, following the Rule of Change: You can only place two pieces next to each other if they differ in just one line:

This not being particularly difficult, you will want to try your hands on the 16 pieces below with four lines.

These puzzles are essentially 1-dimensional and thus force us to think like linelanders. But hidden underneath are are higher dimensions.

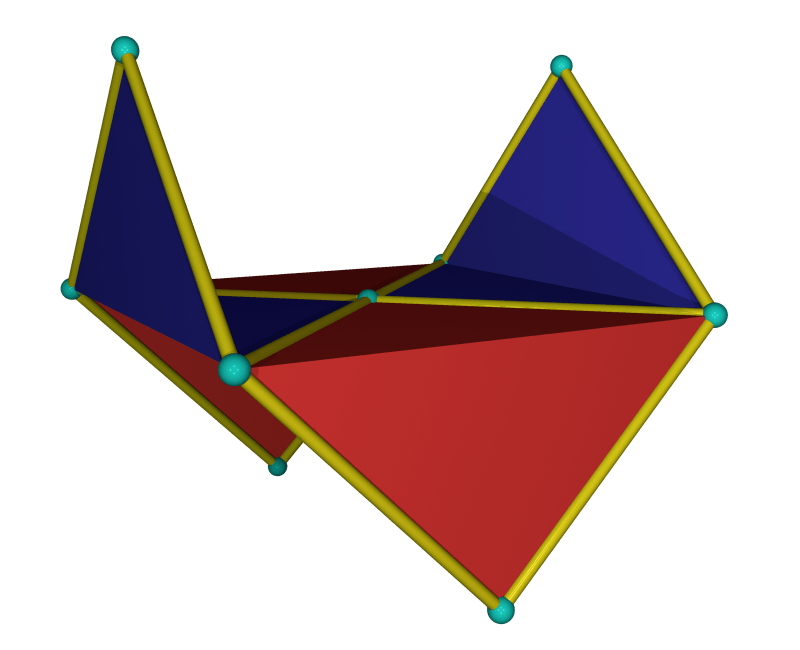

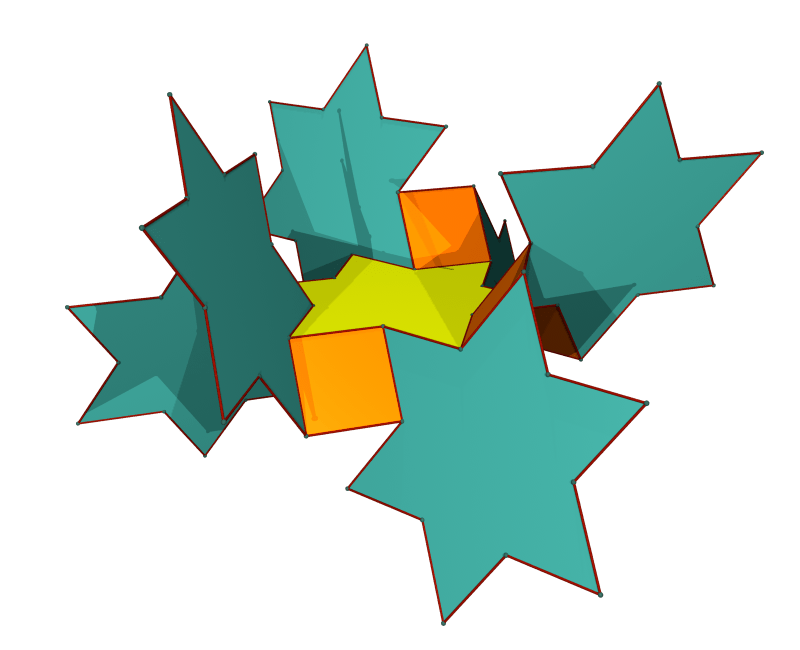

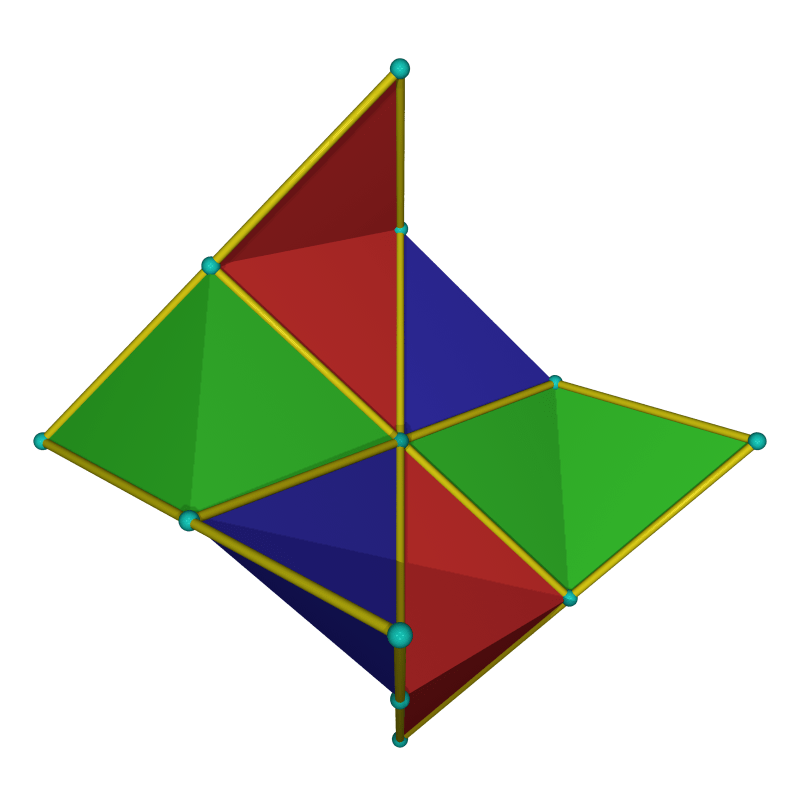

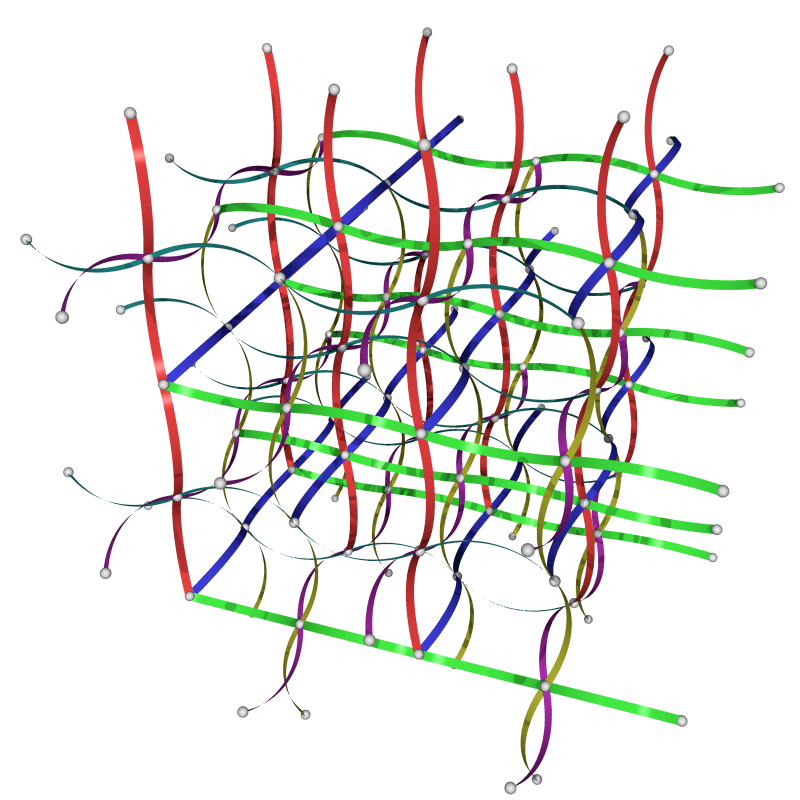

Let’s return to the three line puzzle. Because there are three lines, each piece has only three potential neighbors it can be connected to, and we can visualize the possibilities in 2 dimensions as follows

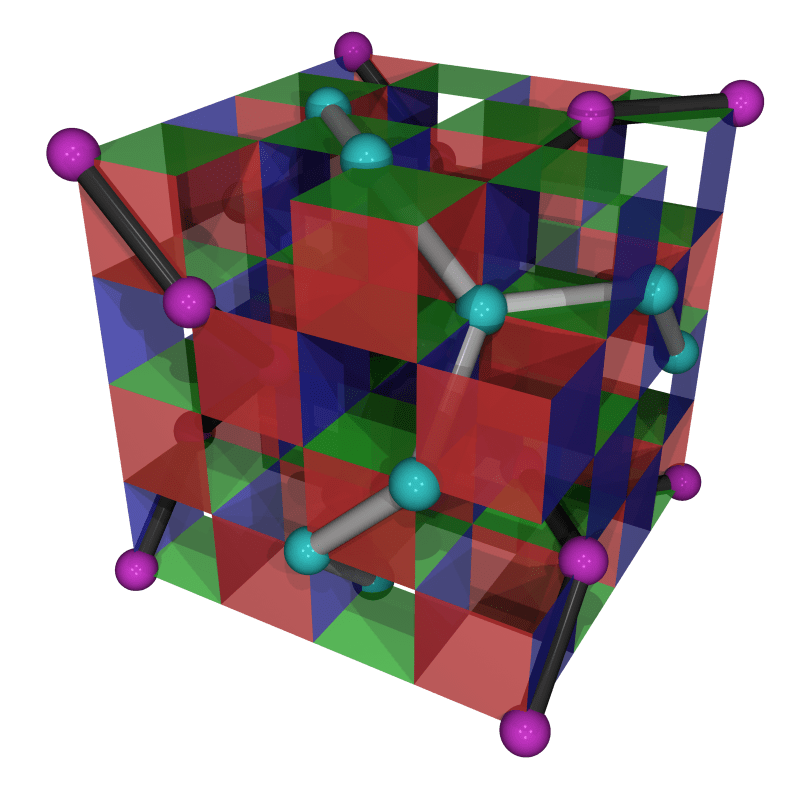

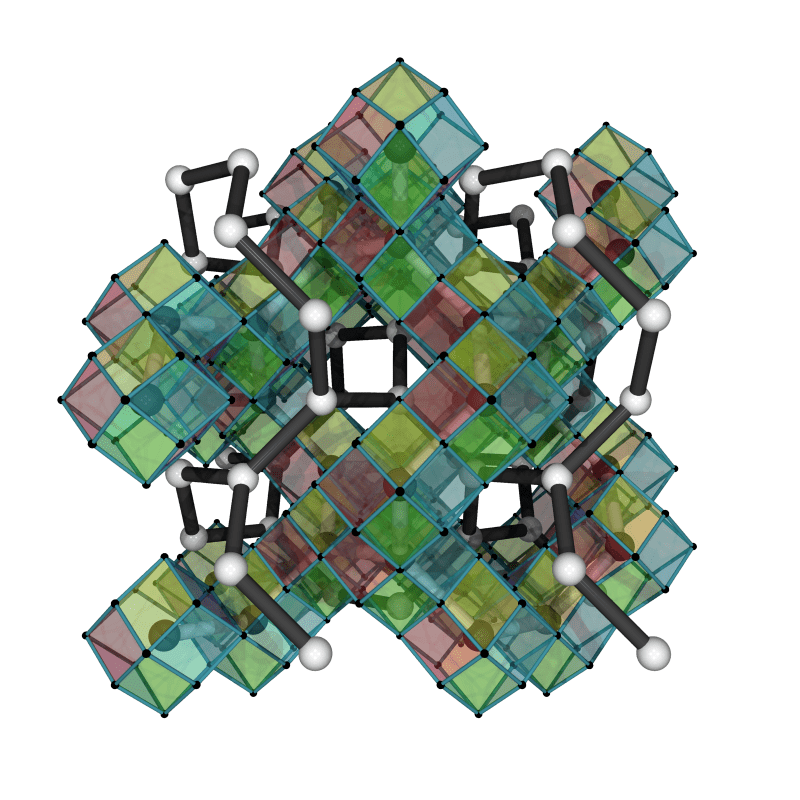

We recognize this as the edge graph of a 3-dimensional cube. This is not accidental: Think of the unbroken lines as zeroes, the broken lines as 1, and each entire symbol as coordinates of a point in 3-space (or 4-space, for the puzzle with four lines).

Two puzzle pieces can only be neighbors if the points differ only in one coordinate, i.e. are joined by an edge of the cube.

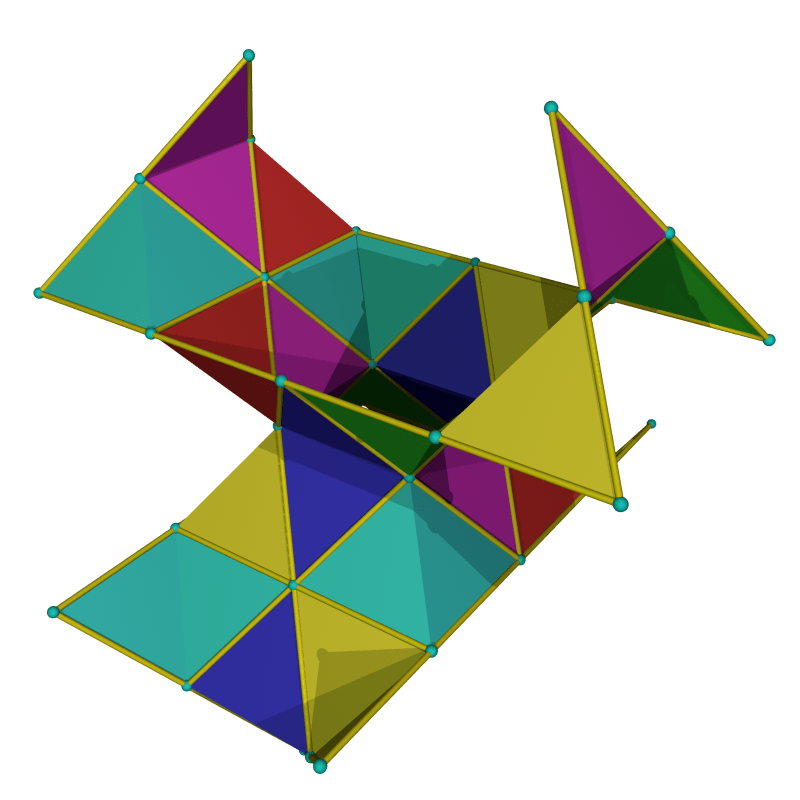

The puzzle asks us to find a Hamiltonian path on this cube (or hypercube), i.e. a closed path that visits each vertex just once.

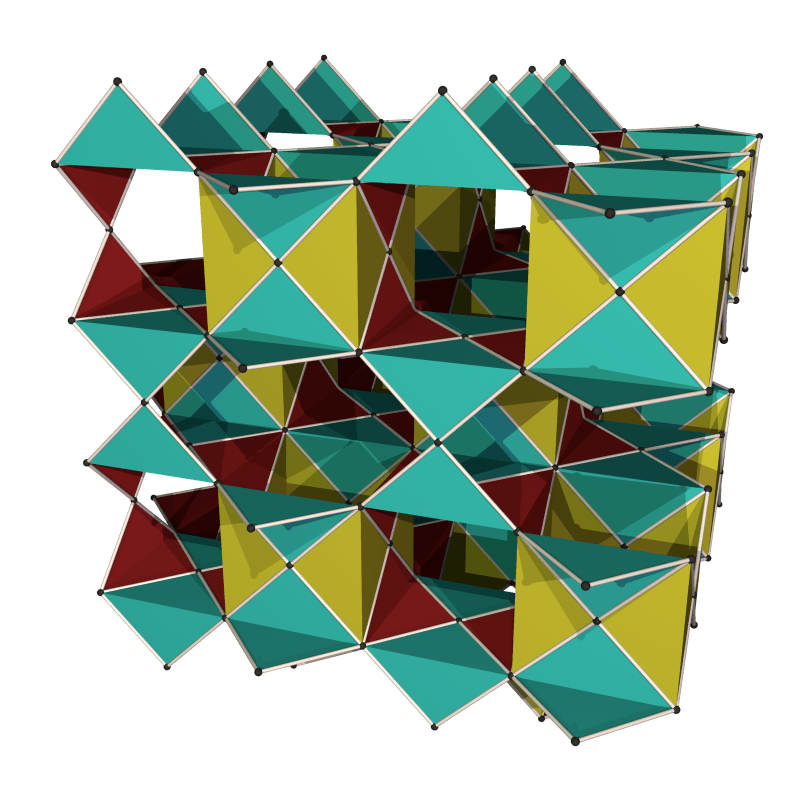

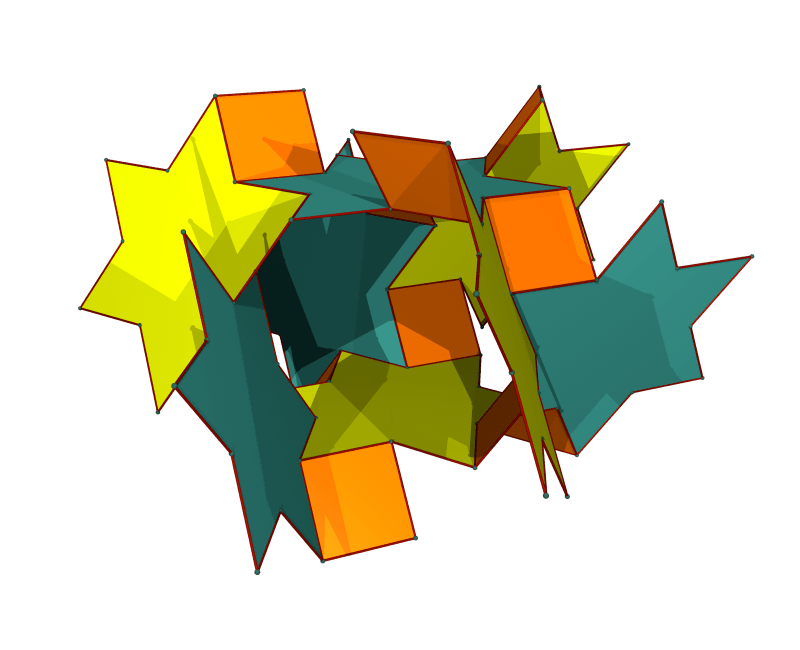

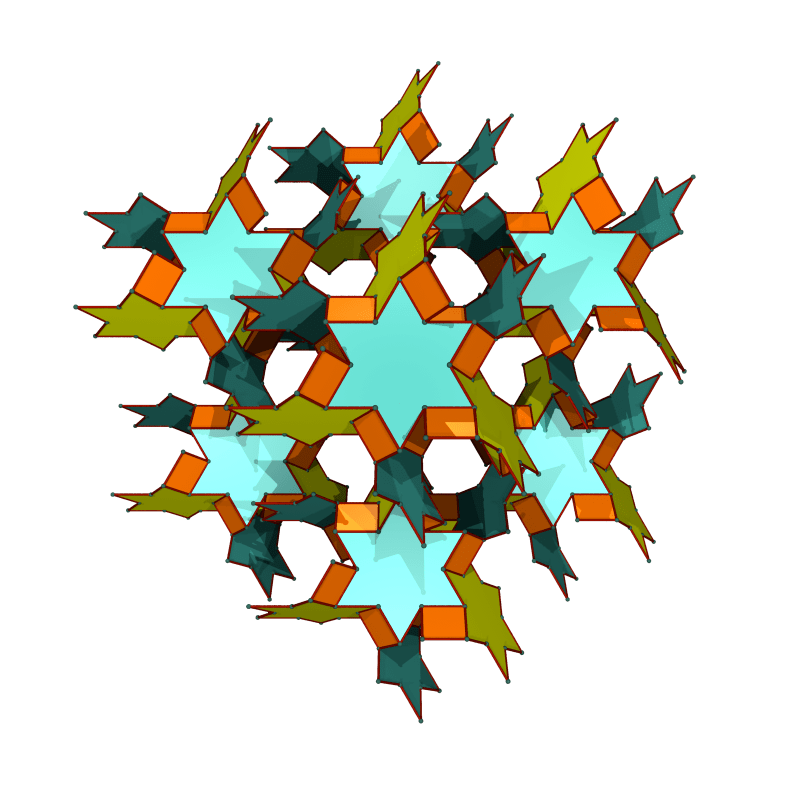

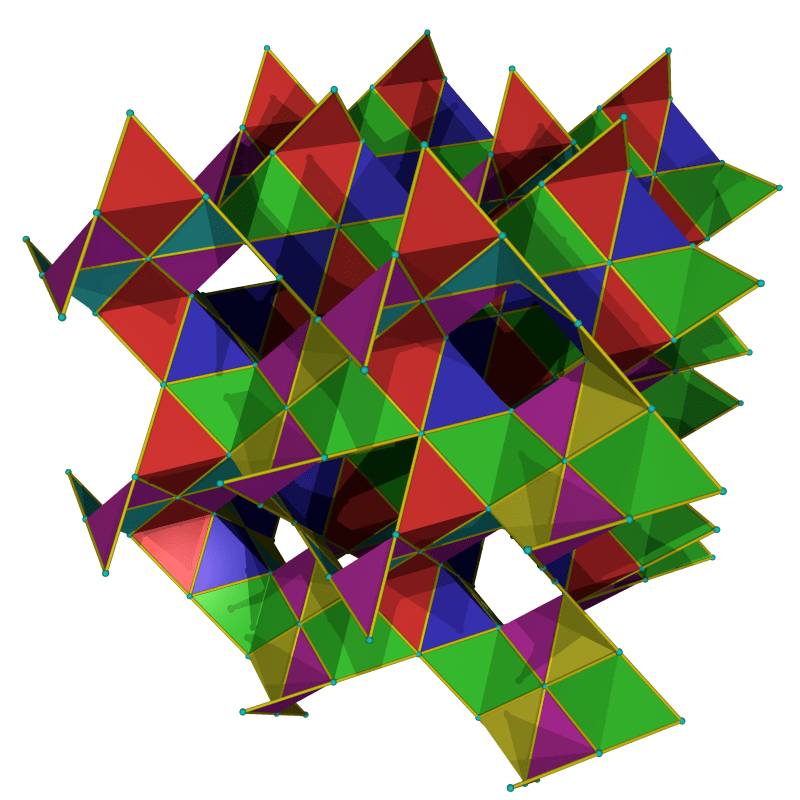

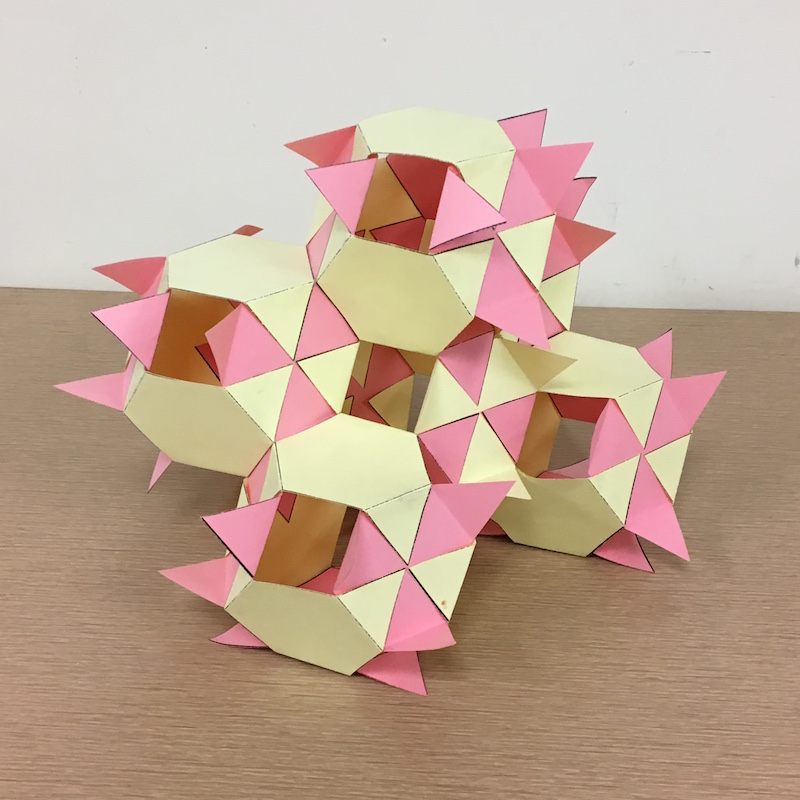

We can now see a solution easily enough. But understanding the underlying structure allows us also to inductively find solutions for the general case of a puzzle with an arbitrary number of lines. For instance, the hypercube can be obtained from the cube by connecting corresponding vertices of two cubes. To find a Hamiltonian path in the hypercube, we can take two identical Hamiltonian paths in the two cube, remove a pair of corresponding edges, and connect the free vertices by edges that connect the two cubes.

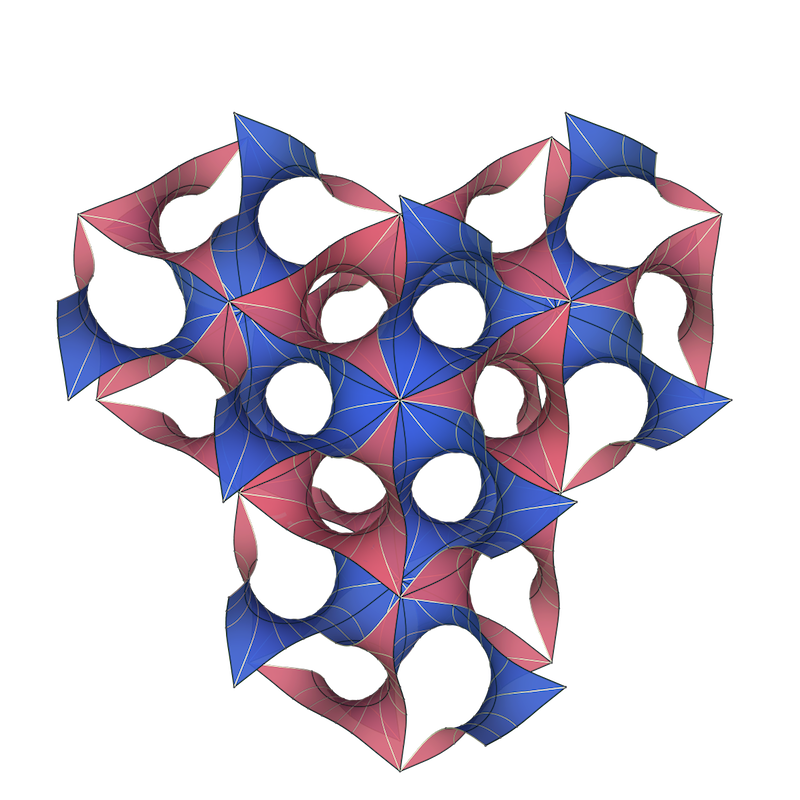

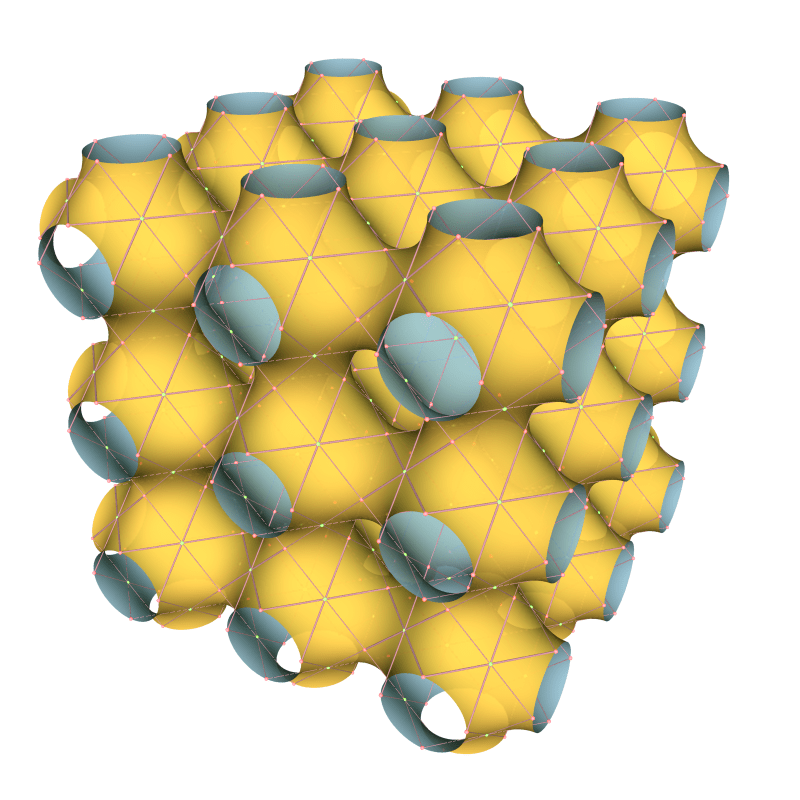

You can now even go ahead and make a puzzle for the complete set of 64 symbols of the I Ching, and find a path

through all of them.