I have written about triply orthogonal surfaces twice before here, in the case of spheres and of cyclides, thus omitting the best known examples, namely that of quadrics. A quadric is for space what a conic is for the plane, and, to warm up, here are some conics ⎯ ellipses and hyperbolas ⎯⎯, all with the same focal points.

That they all meet orthogonally is not difficult to see, one can either use the geometric definition of these conics as curves whose points have constant distance sum/difference to their focal points, or an algebraic description as level sets of quadratic polynomials.

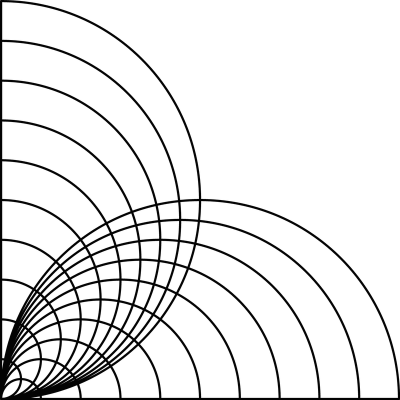

In the plane, there is one other kind of conic, namely the parabola, and here a single family of confocal parabolas provides us already with a doubly orthogonal system of curves:

While the images are pretty, there is nothing astonishing happening here: Any reasonable curve family will allow you to find orthogonal trajectories, and the pigeonhole principle or one’s belief in the pre-established harmony of the universe will force cases where both curve families are simple.

Not so in dimension 3: A surface family in space only belongs to a triply orthogonal system of three surface families if it satisfies a rather complicated partial differential equation, which I believe was first found & used by Jean Gaston Darboux.

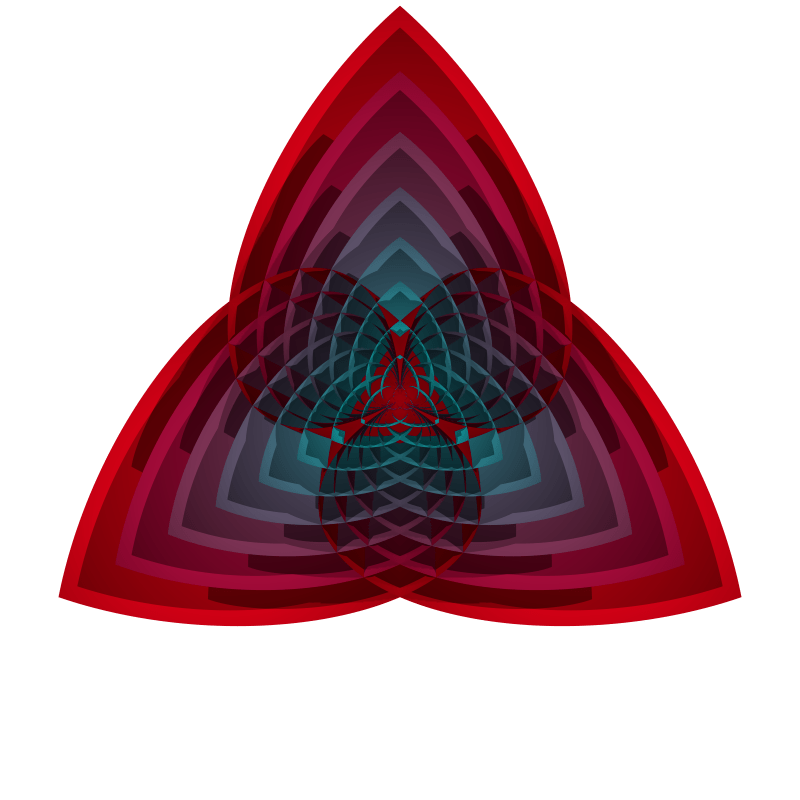

But again there are simple cases, and the algebraic argument that establishes the orthogonal hyperbolas and ellipses above also establishes that their 3-dimensional analogues form a triply orthogonal system of surfaces.

Here you can see all three general kinds of quadric surfaces: An ellipsoid, and the two different hyperboloids. The green one is the so-called single hyperboloid: it continues through the ellipsoid and has only one component. The yellow one is the double hyperboloid and has two components. I have mentioned the single hyperboloid before in connection with Brianchon’s theorem.

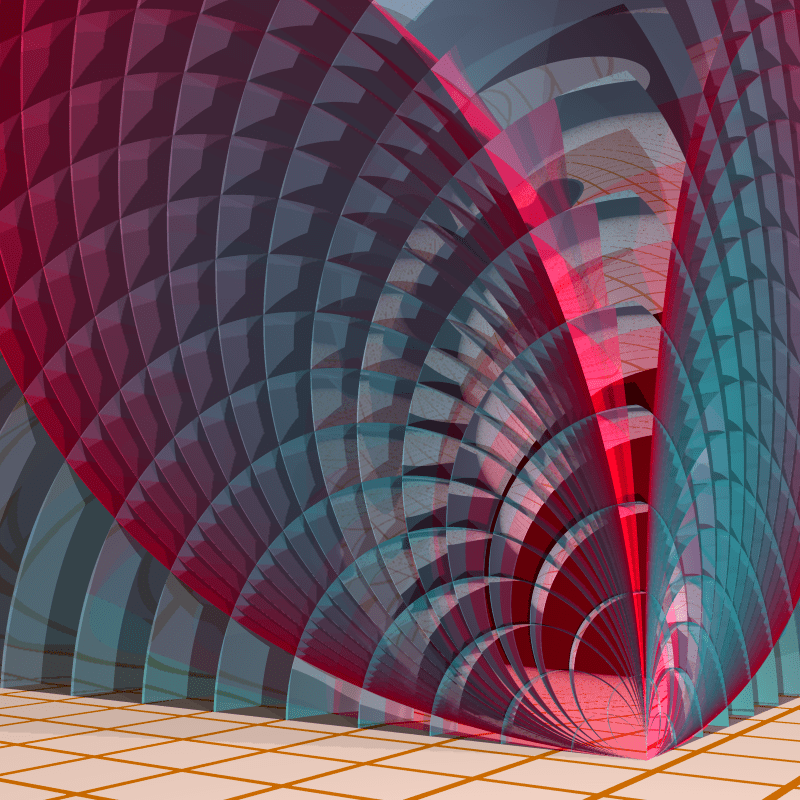

One reward for all these efforts to have them meet orthogonally is that one can see immediately the curvature lines of them, because a theorem of Pierre Charles François Dupin (not to be confused with Edgar Allan Poe’s detective C. Auguste Dupin) says that in triply orthogonal systems, two of the surfaces always meet in a curvature line of the third surface. The following image illustrates this for the ellipsoid: I have clipped the hyperboloids using a slightly larger (invisible) ellipsoid. This looks like it is complicated to make, but in fact requires only a few lines of code in PoVRay, a text based ray tracer that allows you to do constructive solid geometry and simple math, besides many other things.