When in 1873 Victor Hartmann died, Modest Mussorgsky visited a memorial exhibition with his friend’s drawings. Deeply impressed, he wrote a suite for piano – Pictures at an Exhibition.

The Pictures are lost, but the music survived.

Around 1910, Wassili Kandinski painted the first abstract painting. Instead of depicting recognizable things from nature, he painted abstract shapes. He even developed a theory how emotions should relate to abstract colors and shapes.

This brought the visual arts closer to music, and it is maybe not a big surprise that Kandinsky ‘composed’ a ballet for abstract shapes, to be performed to Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

Kandinsky’s ballet is lost, but the idea survived.

In the spring semester 2003, I taught the class Exploring Mathematical Ideas to undergraduates majors and minors at Indiana University in Bloomington, with the idea to recreate a modern version of the ballet, using computer graphics.

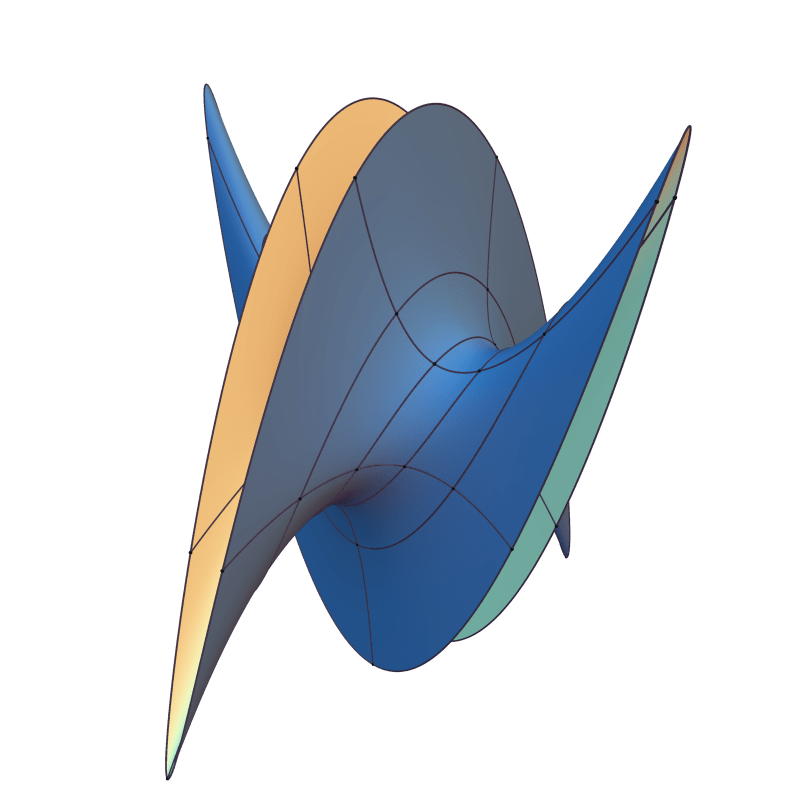

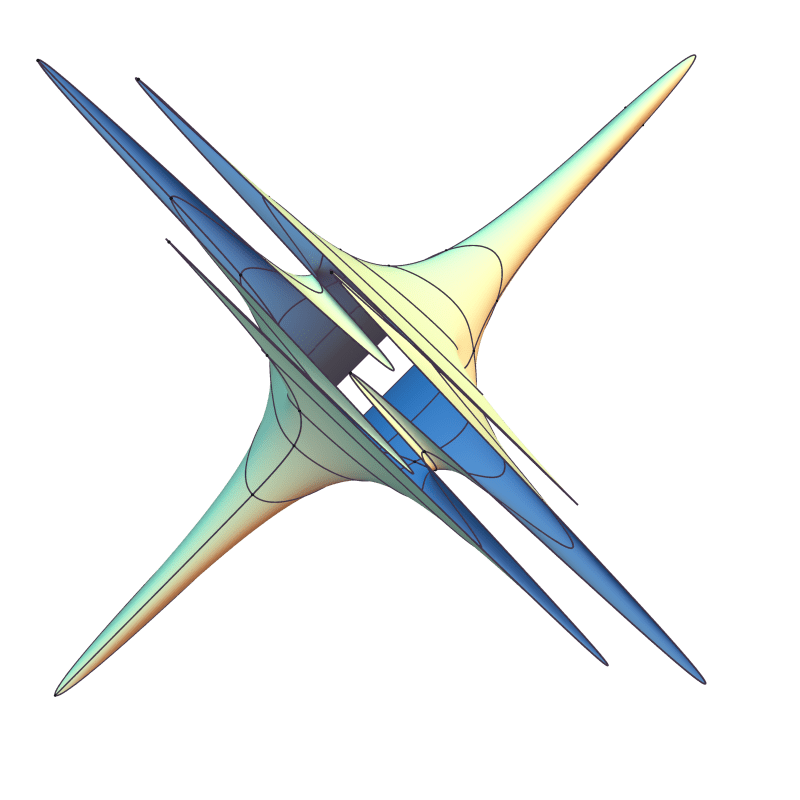

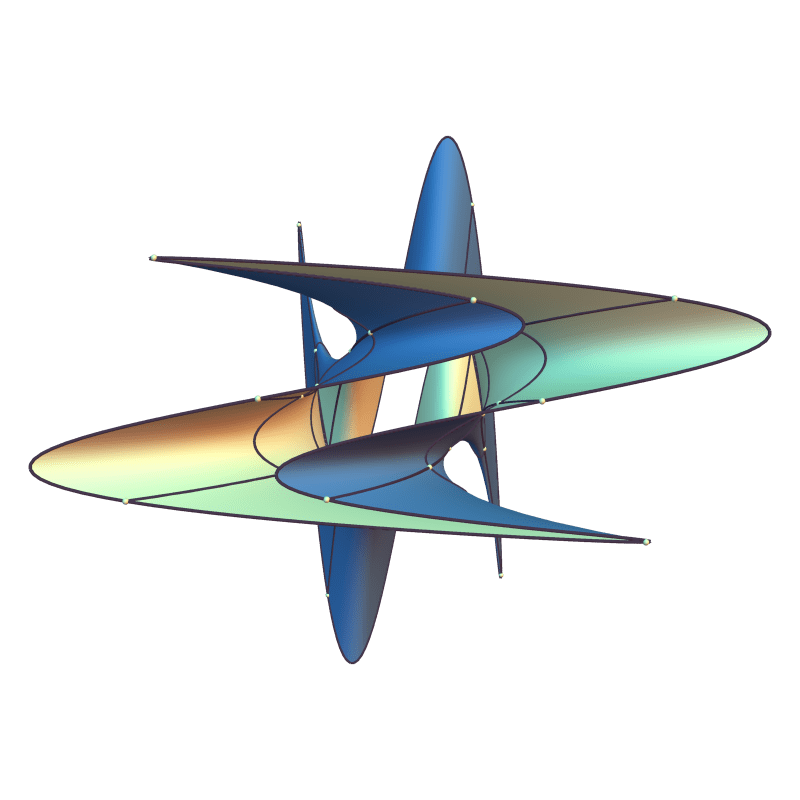

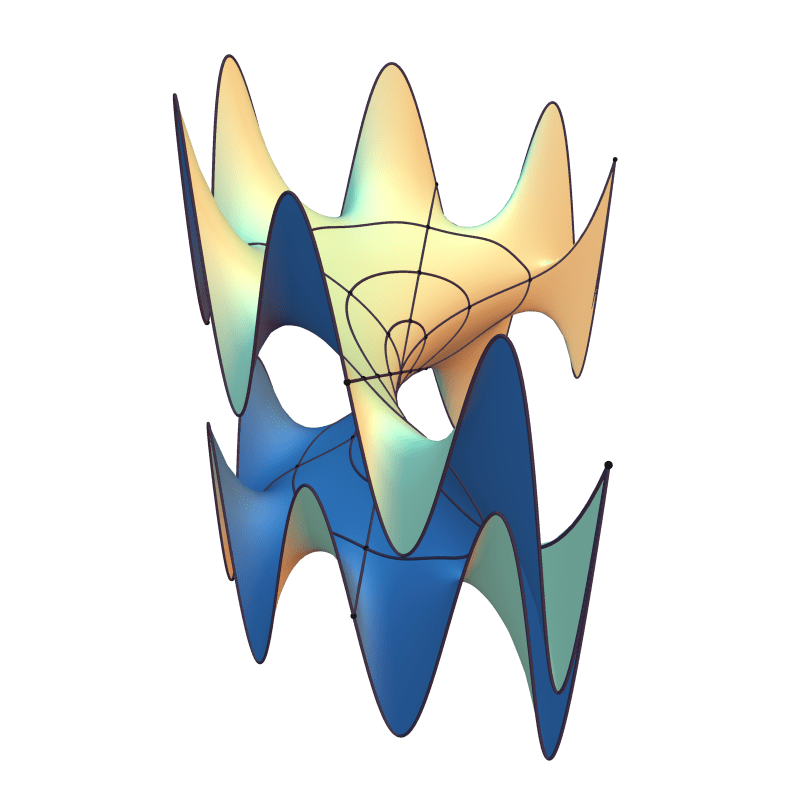

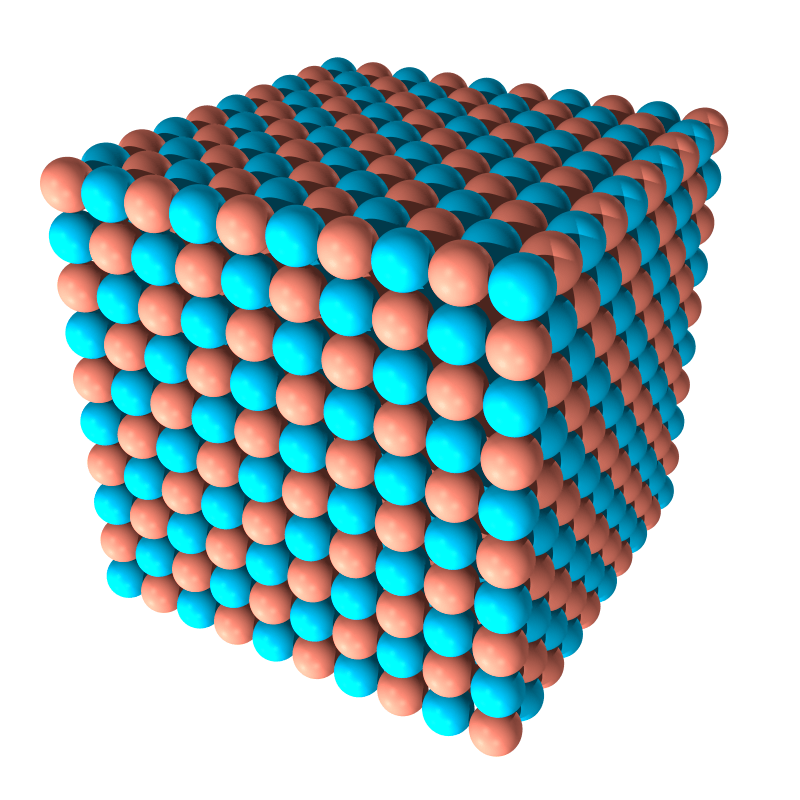

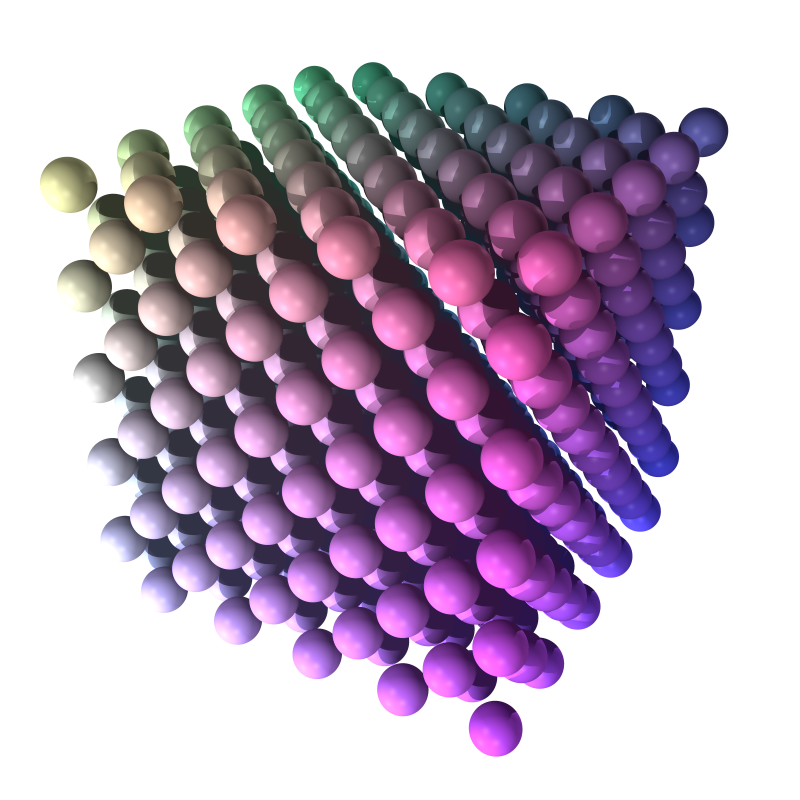

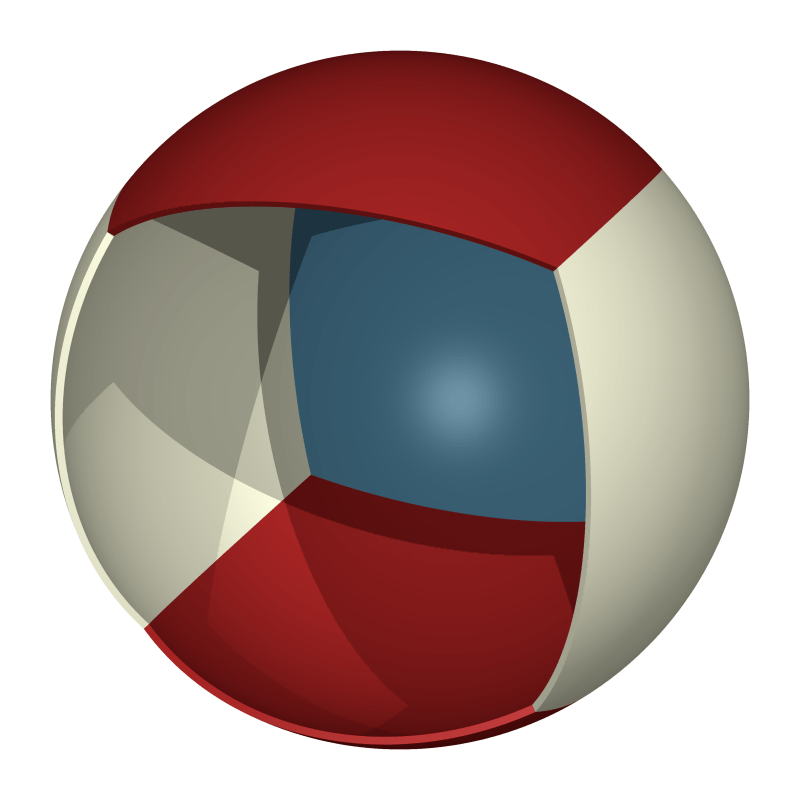

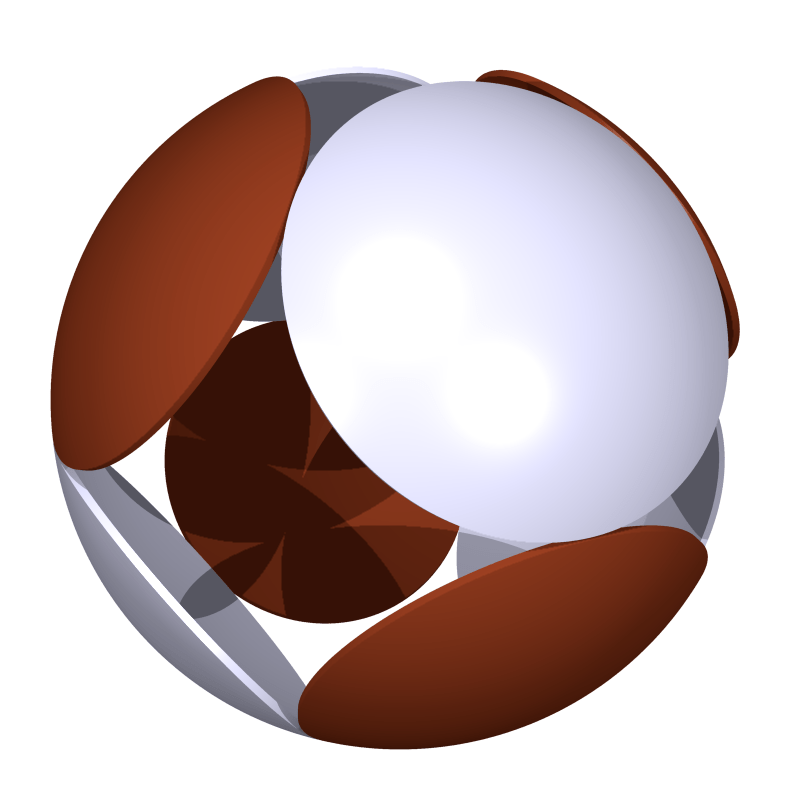

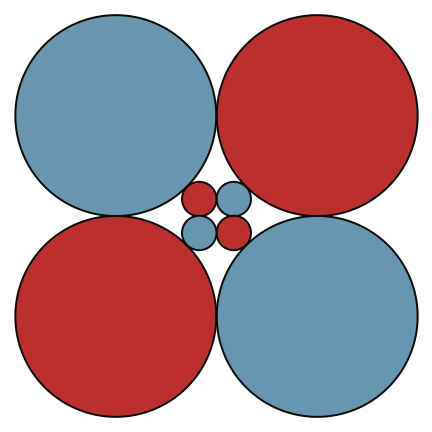

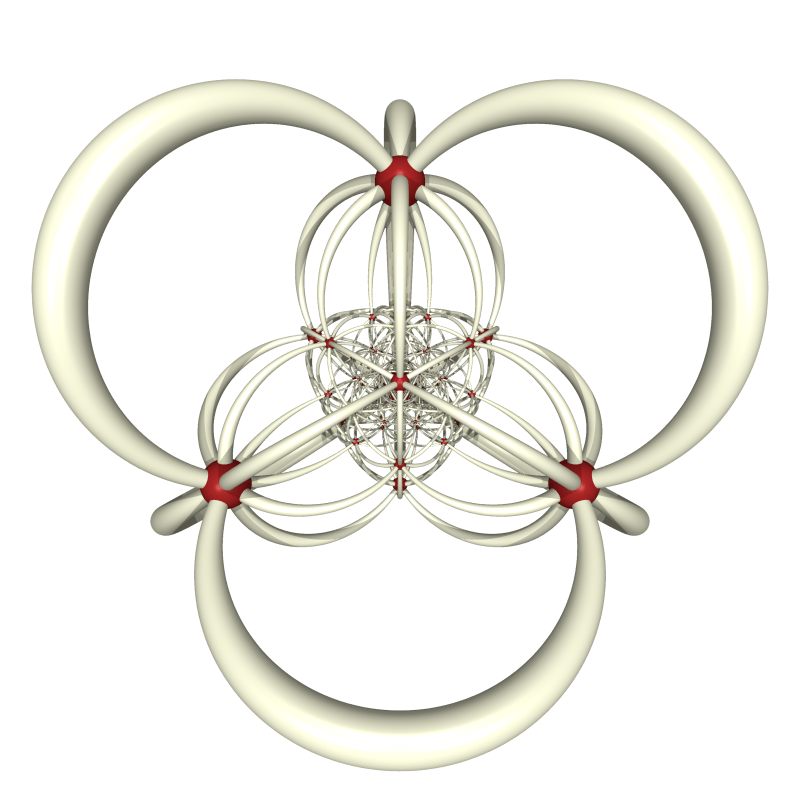

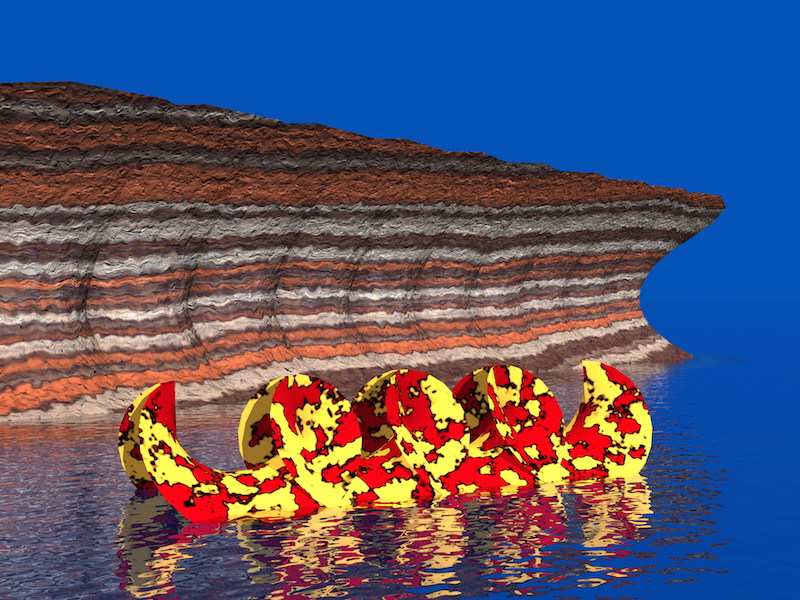

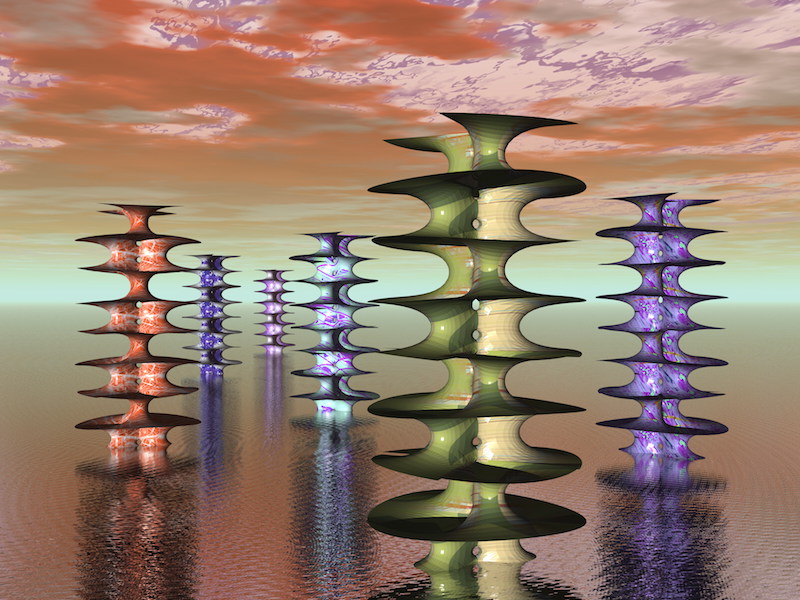

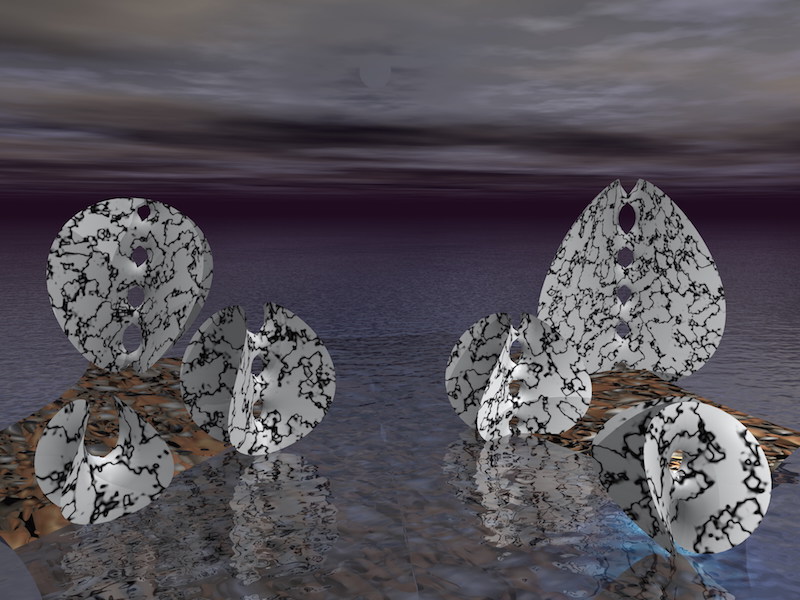

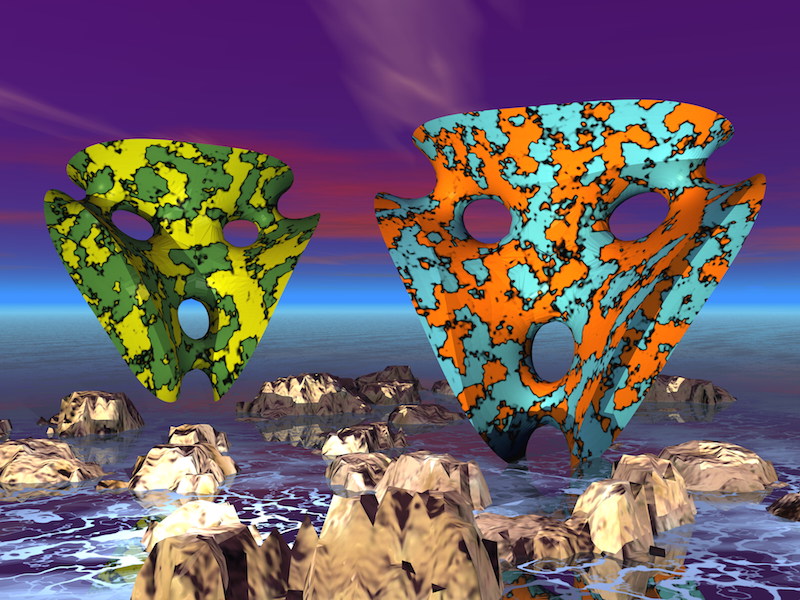

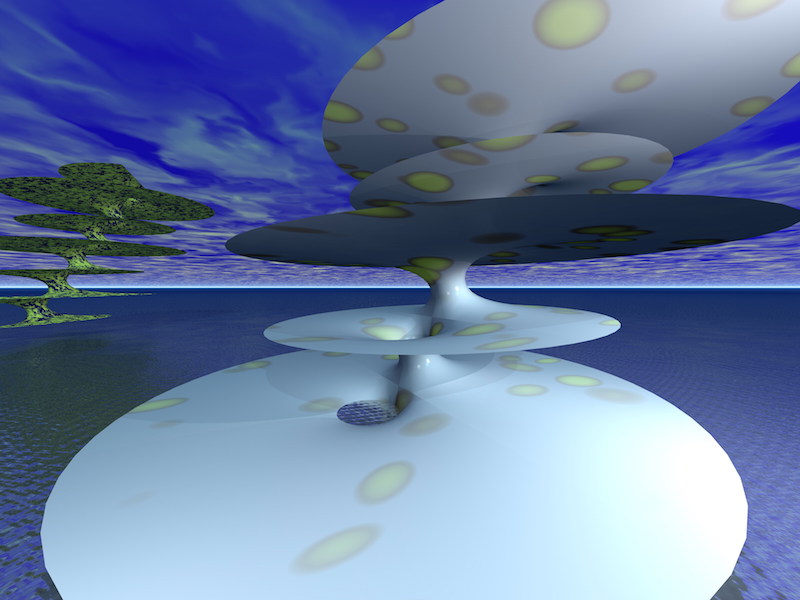

I introduced polyhedra in class early on, and used the raytracer PoVRay as an illustrational tool.

The students had to learn the basics of raytracing with PoVRay in the first half of the class.

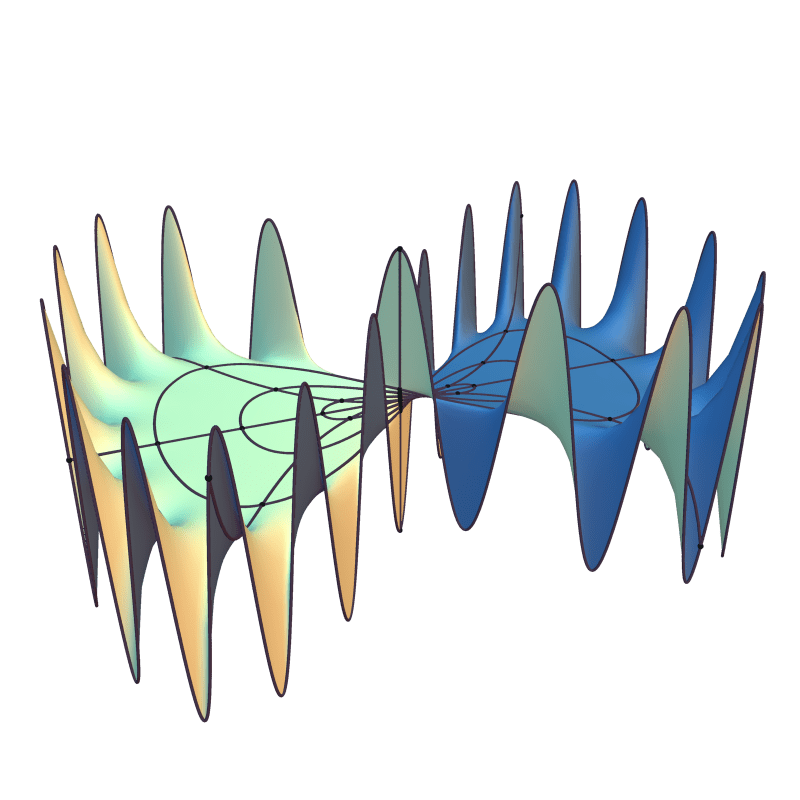

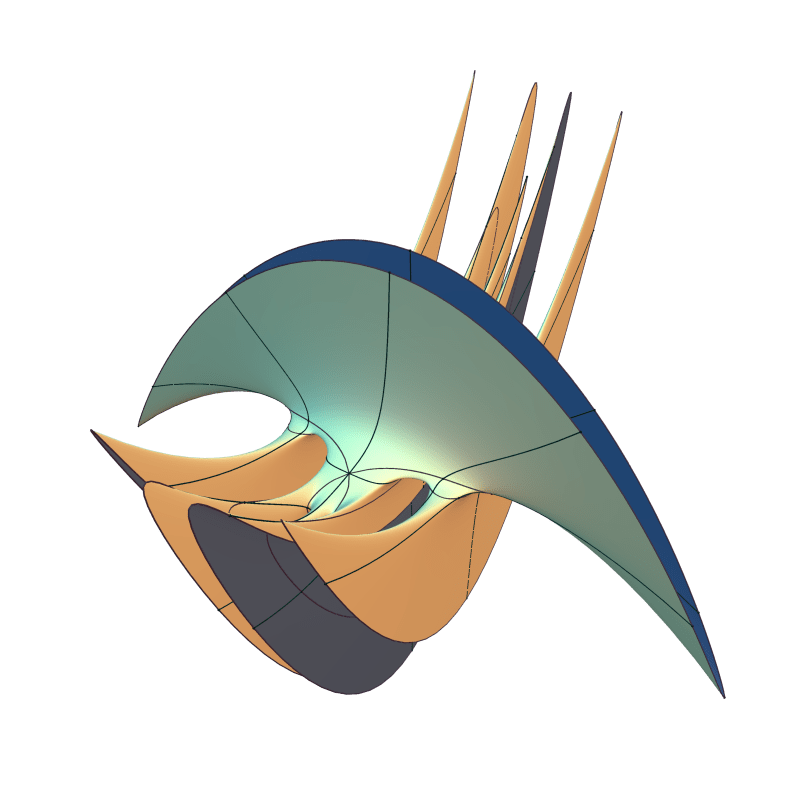

Then we assigned one piece of the music to each student, picked a few polyhedra, created 3D models (in PoVRay), designed a few scenes, and rendered keyframes.

Then we turned to animations: What was a constant (a color, the coordinate of a point, the size of an object) could now suddenly depend on a time parameter.

This proves the concept of a variable instantly useful, and shows that being able to write down formulas for functions allows to control these geometric quantities according to the design of the scene.

How did we synchronize? The answer is: We didn’t. I didn’t ask my students to synch the movie to the music. In fact, it is usually easier to synch the music to the movie by employing a live player, than the other way round. Some of the students tried it nevertheless and succeeded amazingly well.

With some more effort, one would be able to use parameters of the music (like sound amplitude) as an input for the raytracer parameters, but our project was a zero budget project, and we didn’t have the technology.

In particular, this would require the ability to precisely align the video track with the sound track. Our (free) software did not even generate the video tracks to the correct duration…

So, instead the goal was to catch the mood of the scene, and I believe this was quite successful.

How to overcome copyrights? Using Mussorgsky’s music from commercial production so that you can publicly show the movie and distribute it is next to impossible. While Mussorgsky’s piano score is in the public domain, neither the various orchestrations are, nor are any recordings.

I was lucky to find a freely downloadable version of the orchestration by Carl Simpson, recorded by the Ithaca Symphony Orchestra under Hrant Cooper. They all and the publisher gave us permission to use the music for this class, and to show the movie. This was an interesting exercise in copyright law!

That the images on this page are so small has a reason: After a hard drive crash, the sources for the movie scenes were lost. What survives, are these images, and a low quality version of the entire 35 minute movie.